by Dale Henwood GBHA Advisory Council

1.0 Preamble

Money has run US college athletics forever. Athletic programs at big universities are big business! Like any other industry, the schools with the most resources tend to succeed, while the others have had to get creative to survive. Now in its fourth year, the Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) era has undoubtedly revealed that this system, and its inequalities, are changing how schools recruit.

College athletes can now sign a wide range of deals, including product endorsements, social media sponsorships, personal appearances, and hosting events. The possibilities are broad, as long as they comply with NCAA rules and state laws – which are still very murky.

The era of NIL has transformed college sports, giving athletes new opportunities and reshaping the game in big ways. NIL opportunities have become a major factor in recruiting, as high-profile schools with strong brand connections and engaged alumni may offer better earning potential for athletes. This shift could make already competitive programs even more attractive to recruits.

On July 1, 2021, the NCAA officially permitted athletes to benefit from their names, images, and likenesses. NIL has completely changed how athletes choose schools — and it is no longer just about fit or playing time. For Division 1 hockey, the new rules became effective for the 2025-2026 season.

2.0 History of the new NIL rules*

Over the years the NCAA has faced mounting pressure from legal cases, state laws, and public support for athlete compensation. For decades, the NCAA held tight to one rule: “no pay” rule – college athletes could not earn money from their sports. That meant no sponsorships, no paid endorsements, and no way to make money from things like autographs or personal appearances. The idea was to keep college sports purely about education and competition.

The concept of amateurism has long been a cornerstone of college athletics, even though the IOC completely abandoned the word “amateur” from the Olympic Charter in the 1990s. This “holier than thou” attitude meant that CHL players were considered “pros.” (see insert below). But as college sports grew into a multi-billion-dollar industry, with games filling stadiums and attracting millions of viewers (especially basketball and football), people started questioning the fairness of this rule.

The push for change really took off in the early 2000s with a series of legal cases. One of the biggest cases came from former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon, who argued it was not fair that the NCAA made money from using players’ likenesses in video games while players received nothing. The case went all the way to court, and in 2014, a judge agreed with O’Bannon, ruling that college athletes should be allowed to profit from their own names and images. This was a huge win for athletes and sparked a movement for more changes.

As the debate heated up, individual states started passing their own laws to allow athletes to profit from their NIL. In 2019, California led the charge with its “Fair Pay to Play Act,” which gave college athletes the right to earn money from endorsements, starting in 2023. Other states quickly followed, putting pressure on the NCAA to change its rules across the board. Faced with mounting legal battles and a growing wave of public support, the NCAA had little choice but to reconsider its long-standing ban on NIL compensation.

Beyond legal and financial pressures, the culture around athlete rights was changing. College athletes now had powerful voices on social media, and they used these platforms to call for greater rights and fair treatment. It became clear that today’s athletes will not settle for the same limitations as previous generations.

This early history set the stage for what would become one of the biggest shifts in college sports. Without the efforts of trailblazing athletes, key court rulings, and state legislation, the NIL opportunities we see today might never have come to life. With state laws threatening to bypass NCAA rules, and a pivotal Supreme Court ruling in 2021, the NCAA had little choice but to allow NIL opportunities for athletes.

Two additional key pieces of legislation reshaped the college landscape.

a. NIL rules. Since 2021, NCAA athletes have been allowed to earn from endorsements, appearances, and social media so long as they stay within school and state guidelines. That alone put college hockey on a different financial footing than it had for most of its history.

On June 21, 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a district court ruling in NCAA v. Alston, which found that the NCAA’s rules limiting student-athlete compensation violated antitrust law. As a result, the NCAA allowed athletes to receive compensation for their status as players.

At that time, however, it is said that the NCAA lacked overall preparation for NIL and they provided little in terms of guidance or restriction. They were working on the rules, but they never got implemented before the Supreme Court’s Alston decision was rendered.

b. In June 2025, the House v. NCAA settlement went through. A federal judge approved a $2.8 billion antitrust deal that allows Division I schools to share revenue directly with athletes, up to roughly $20.5 million per year starting in 2025–26. Many schools will funnel most of that toward football and basketball, but the settlement makes revenue sharing part of the normal vocabulary for every DI athlete, hockey included.

[* for a more in-depth look at related legislation, see Appendix 1].

3.0 Transfer Portal Described

The NCAA Transfer Portal is a centralized, NCAA-managed database that allows student-athletes to formally declare their intention to explore transferring to another NCAA institution. Once an ice hockey student-athlete enters the portal, their current institution is notified, and other NCAA programs are permitted to contact them for recruiting purposes. Entry into the portal does not obligate an athlete to transfer, but it signals openness to new opportunities.

For men’s and women’s ice hockey, the portal operates within defined transfer windows and is shaped by broader NCAA policy changes, including the relaxation of transfer restrictions and, in many cases, immediate eligibility upon transfer. These changes have materially altered roster management and competitive dynamics across college hockey.

3.1 Portal implications for hockey include:

1. Increased Roster Volatility

The transfer portal has significantly reduced roster stability. Programs experience greater year-to-year turnover, with athletes moving for increased ice time, coaching changes, academic fit, NIL opportunities, or competitive aspirations. This has compressed recruiting cycles and made roster continuity more difficult to maintain.

2. Acceleration of Free-Agency Dynamics

College hockey increasingly resembles a free-agent marketplace. Experienced players with proven performance are highly valued, often prioritized over traditional freshman recruits. These shifts recruiting emphasis from long-term player development to short-term roster optimization.

3. Competitive Stratification

Well-resourced programs—particularly those big schools or with strong NIL collectives—often have a competitive advantage in attracting portal athletes. Mid-major and development-oriented programs risk becoming net “exporters” of talent.

4. Development vs. Retention Tension

Programs that excel at developing players may see those athletes transfer once they mature into impact contributors. This challenges the traditional development model and places pressure on coaching staffs to balance opportunity, communication, and retention strategies.

5. Impact on International and Junior Pathways

The portal has indirect implications for Canadian and European pathways, including U SPORTS and major junior. As NCAA rosters recycle experienced transfers, fewer entry-level roster spots may be available for incoming freshmen or international recruits, altering decision-making across the hockey ecosystem.

6. Administrative and Compliance Burden

Managing portal activity requires increased administrative oversight, compliance diligence, and athlete support. Coaches and administrators must navigate transfer timing, eligibility rules, scholarship management, and academic continuity.

For hockey programs, the transfer portal is no longer a peripheral mechanism—it is a core roster management tool. Successful programs are adapting by:

- Treating retention as strategically important as recruitment and NIL is a key factor on retention.

- Enhancing athlete communication and role clarity.

- Integrating portal planning into long-term program design.

- Aligning development philosophy with realistic transfer risk.

In summary, the NCAA transfer portal has fundamentally reshaped college ice hockey, introducing both opportunity and instability. Programs that adapt strategically and proactively are best positioned to manage its long-term effects.

4.0 The NCAA is BIG Business

Revenue-generating programs play a critical role in elevating the profile and national visibility of the University and its schools. Through extensive media exposure—particularly television and broadcast partnerships—these programs enhance institutional reputation while also delivering significant, sustainable revenue that supports the broader academic and athletic mission of the University.

Across US universities, revenue generated by high-profile sports programs is commonly reinvested well beyond athletics. Typical examples include:

- Academic and Research Facilities: Surpluses from television contracts, sponsorships, and ticket sales are often directed toward constructing or renovating classrooms, laboratories, and research centres, particularly in STEM, health sciences, and professional faculties.

- Student Services and Support Programs: Athletic revenues can help fund scholarships, bursaries, student mental health services, academic advising, and career development programs that benefit the broader student population.

- Campus Infrastructure: Revenue from sport is frequently used to support major capital projects such as student unions, libraries, residence upgrades, and multi-use recreation and wellness facilities.

- Non-Revenue Sports and Recreation: Profits from marquee sports subsidize varsity programs that do not generate revenue, as well as intramural and recreational sport programs that contribute to campus health and student engagement.

- Community and Outreach Initiatives: Some institutions allocate athletic revenues to Indigenous engagement, community partnerships, youth sport programs, and outreach initiatives that strengthen town–gown relationships.

- Institutional Operating Budgets: In certain cases, athletic departments contribute directly to central university budgets, helping offset operating costs and reduce pressure on tuition or public funding.

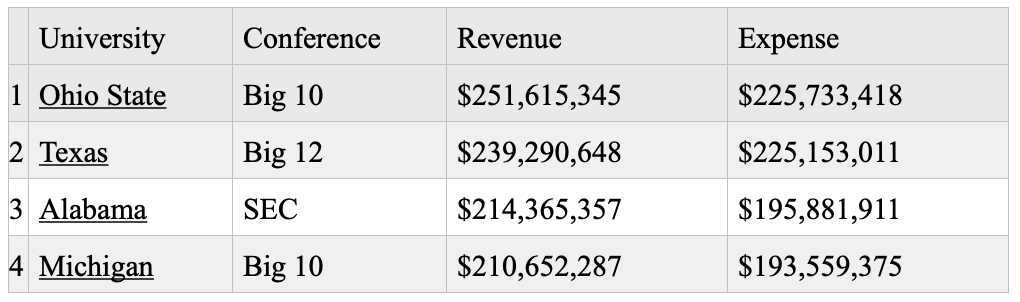

Collectively, these investments demonstrate how sport-related revenue can function as a strategic financial engine supporting academic excellence, student experience, and long-term campus development. As an example, the athletics revenue (2024) of the top 4 schools is depicted below.

(NCAA Finances: Revenue & Expenses by School – USA TODAY https://sportsdata.usatoday.com/ncaa/finances)

It is interesting to note that these revenues are similar to the investment the Government of Canada, through Canadian Heritage/Sport Canada, provides to the entire Canadian sport system.

There are currently 50 schools with revenues over $100M. annually.

The NCAA reported a record $1.38 billion in revenue in fiscal 2024, and the vast majority of it came from one contract: its partnership with CBS and Turner to broadcast the men’s March Madness tournament. (NCAA’s FY24 Revenue Sets Record, Offset by $3B in Liabilities).

The men’s hoops championship has for years been the NCAA’s most valuable financial asset; the NCAA does not control the College Football Playoff, nor any top-tier bowl games. The three weeks of March Madness fund the NCAA’s operations and the bulk of the hundreds of millions that the NCAA distributes each year to its member schools and conferences.

In recent years, however, amid sweeping changes, the NCAA has pushed to diversify its income streams. In fiscal 2015, the Turner/CBS deal made up nearly 80% of the NCAA’s revenue, according to the NCAA’s audited financial statements. In fiscal 2024, that was down to 63%. Over that span, NCAA revenue from areas beyond the men’s tournament media rights grew from $192.3 million to $503.6 million.

The NCAA receives most of its annual revenue from two sources (Television and marketing rights and Championship Tournaments). That money is distributed in more than a dozen ways – all of which directly support NCAA schools, conferences and nearly half a million student-athletes. (Where Does the Money Go? – NCAA.org

https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2016/5/13/where-does-the-money-go.aspx).

The NCAA does not receive funds from the Division I College Football Playoff and football bowl games. These events are independently operated. Division I College football draws revenue from several primary sources, including media rights deals, ticket sales, sponsorships, merchandising, donations, and participation in major postseason events like the College Football Playoff. The NCAA and its member schools benefit significantly from substantial television contracts, which form the backbone of financial support for both conferences and individual athletic departments.

Recent reports highlight that the NCAA itself generated $1.4 billion in annual revenue, with a substantial portion attributed to college football broadcasting rights. The top teams from the five conferences (SEC, Big Ten, ACC, Big 12, Pac-12) plus Notre Dame and SMU are projected to make over $7.4 billion in fiscal year 2025-26 and as much as $10.5 billion by 2034-35 (NCAA).

A caveat. Resources do not always equate to success. For example, no current Big Ten hockey school has won the NCAA men’s hockey national championship in the past 15 years. So, even the schools with resources (primarily from football and basketball) it does not always translate to winning.

5.0 The Power of Giving

Philanthropy via Alumni connections has long shaped the landscape of American higher education. From endowment‑building gifts that transform research capacity to alumni‑driven support that fuels athletic excellence, donations play a defining role in how universities compete, innovate, and build legacy.

Two areas consistently attract the largest philanthropic commitments:

a. Overall institutional giving, which strengthens academics, research, and infrastructure.

b. Athletic‑specific alumni giving, which drives competitiveness, facilities, and student‑athlete experience.

Athletic fundraising is driven by passionate alumni, competitive traditions, and the cultural weight of college sports in the USA. Athletic identity drives alumni passion. (Football‑centric schools often dominate athletic fundraising regardless of the school’s academic rank). Donor culture is self‑reinforcing, where success — academic or athletic — attracts more investment, which fuels more success.

Even the strongest U SPORTS programs operate on a completely different financial planet.

NCAA fundraising is often about facilities and winning. In U SPORTS, the strongest play is often: leadership development, life outcomes, community impact, and the deep relationships formed in these programs.

For Canadian universities, a strong athletic program is often framed as attracting driven student-athletes and building campus spirit while differentiating one University from others, in a crowded market.

6.0 Collectives**

Many schools have developed “collectives,” which are independent of a university, and are groups that most often pool funds from boosters and businesses to help facilitate NIL deals for athletes and also create their own ways for athletes to monetize their brands.

Overall, alumni tend to recognize the importance of recruiting and use their personal wealth as leverage to not only attract but also maintain a roster. Because of this, collectives have illustrated the lengths that alumni and schools are willing to go to build a skilled team.

There is a direct correlation between booster generosity and substantial success in recent years.

According to total cumulative “donations and contributions” findings from 2005 through the end of the 2022 season via USA Today and the Knight Commission, programs who receive the most donor funds tend to have a heightened advantage against others through recruiting success, coaching prestige, facility enhancements and other upgrades.

It is no secret that college football recruits are signing as high as 7-figure NIL deals. While extremely high deals are not indicative of 99% of opportunities for student-athletes, the expensive deals that certain recruits are being offered is something that has been extremely noteworthy this year.

** [An NIL collective is an independent organization—usually created by a school’s boosters, alumni, and local business leaders—that pools money to fund Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) opportunities for student‑athletes at a specific university.

Core characteristics:

- Independent from the university (schools cannot directly run NIL deals)

- Funded by donors, alumni, businesses, and fans

- Creates and manages NIL deals such as social media promotions, appearances, camps, charity events, endorsements, etc.

- Provides a centralized system so athletes do not have to negotiate dozens of individual deals on their own

- Must comply with NCAA rules (no pay‑for‑play, no recruiting inducements, fair‑market‑value work required)].

7.0 NIL Implications for hockey

In July, 2025 Penn State landed Gavin McKenna, the projected first overall pick in the 2026 NHL Draft and reigning CHL Player of the Year, on a reported six-figure ($750,000 USD) NIL or endorsement package that ESPN has called the biggest in college hockey to date. (College Hockey’s NIL Money Is Rewriting the Finnish Prospect Path to the NHL – The Hockey Writers – College Hockey – NHL News, Analysis & More).

Another profile example is Porter Martone to Michigan State for a reported $250,000, though the distribution over eligibility was unclear (i.e. per year or over 4 years?). After that, for hockey, the dollars fall off a cliff.

With NIL, player can make money from:

-

Social media brand partnerships

-

Endorsements with local businesses

-

Sponsored appearances and camps

-

Merchandise sales and personal branding

-

Digital content creation, from podcasts to training videos

At present, a player may get paid to teach at a hockey school or paid to produce a Tik Tok video ($1,000 to $5,000 for a video).

Initial data suggests that in the first recruiting cycle after the change, roughly one-third of incoming DI freshmen had CHL experience, and more than 80% of Division I teams dipped into the CHL pool to upgrade their rosters. Put that beside NIL and House, and the picture is simple: college hockey now has more money and a bigger talent pool.

Unlike football and basketball, there is no publicly available list of NIL compensation for players, Canadian or otherwise, transferring into NCAA Division I hockey (even though disclosure of the existence of deals is now required). The data simply is not disclosed anywhere as NIL deals are negotiated privately between players, their advisors, and NIL collectives/sponsors. Anecdotal stories and rumors on compensation seem to be exaggerated, however, it is abundantly clear that hockey is in a different league than football and basketball regarding NIL packages.

Important Notes:

- Hockey is lower visibility compared to major sports, so only a small fraction of players receives large NIL payouts.

- Compensation via NIL is separate from base athletic scholarship, which at NCAA Division I hockey often covers tuition and related costs; NIL is extra compensation for marketing rights.

- Canadian citizens and international recruits face potential cross border tax and visa considerations that can affect NIL deal structures.

- Many NIL deals include performance incentives, brand partnerships and other terms that are not publicly disclosed unless the player or program chooses to reveal details.

While there are no player‑specific numbers, there are contextual indicators:

- NIL is now another piece in the recruiting and retention process.

- NIL deals for hockey players vary widely.

- NIL now offers some “salary” but without transparency.

- Based on very limited reporting, high‑end transfers receive $25k–$75k, while most players receive below $10k, often gear, appearances, or small endorsements. But again — these are estimates, derived from personal conversations with league executives, but not published numbers.

- Biggest impact will be felt on U SPORTS and tier 2 junior leagues (BCJHL and AJHL) as well as the USA Hockey National Team Development Program (Men’s national under-18) and the USHL (top junior league in the USA).

NCAA hockey is undergoing “truly seismic changes” driven by NIL money and the transfer portal, which are giving big‑budget programs new advantages over smaller ones. The portal is now a “searchable recruiting marketplace” with thousands of athletes entering each year. The portal has turned NCAA hockey into a constantly shifting roster marketplace, where players move to chase opportunity or are displaced by new recruits. The recruiting shift does not just relate to NCAA scholarships, but with NIL‑enhanced packages.

For U SPORTS, this means more Canadian players may choose the NCAA because there is some financial incentive along with greater exposure to scouts and a perceived better path to a professional career. The financial incentive, as limited as it may be, is something U SPORTS cannot match under its current rules. Also, factually, U SPORTS has not housed NHL bound players and this will not change. The level of U SPORTS play must go down because many of the CHL players they would have received will be going stateside. Unless there is a specific academic area of interest for an athlete, the new challenges will be difficult for U SPORTS. Early information suggests that over 190 CHL players are scheduled to leave the CHL for NCAA next year while these players have CHL eligibility remaining – this has a significant negative impact on U SPORTS.

For the Golden Bears, this means they cannot compete financially with NCAA offers and must recruit and differentiate on culture, playing time (development), education, and the programs’ identity as a stable, elite, tradition-rich program.

8.0 Another challenge?

In what will be a landmark shift across collegiate hockey, NCAA Division III programs are expected to announce they will begin welcoming former Canadian Hockey League (CHL) players to their rosters starting with the 2026–27 season. (https://thejuniorhockeynews.com/ncaa-diii-hockey-programs-move-to-accept-former-chl-players-starting-in-2026). The move represents a significant evolution in Division III hockey and expands academic and athletic opportunities for elite junior players seeking a college pathway, provided they did not receive compensation beyond “actual and necessary” expenses. Eligible players will need to meet NCAA academic eligibility requirements and can not have signed a professional contract.

Like the NCAA Division I decision in 2024 which was made under the cloud of a class action lawsuit filed by former CHL players, it is reported that multiple players with CHL experience were considering similar litigation against Division III.

9.0 Appendix 1

When Did NIL Deals Start? Key Moments in College Sports History — GAME CHANGE (https://www.gogamechange.com/blog/when-did-nil-start).

The road to NIL rights was not an overnight journey; it took decades of persistence, legal battles, and changes in public opinion to make it happen. Here are some of the major milestones that paved the way for NIL’s historic launch in 2021.

- 1956 – NCAA begins to allow student-athletes to receive athletic scholarships without regard for their academic ability or financial hardships.

- 1975 – The NCAA updated its regulations limiting scholarships to tuition, books, and board.

- 1984 – In a 7-2 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that the NCAA’s control of college football television broadcast rights violated the Sherman and Clayton Antitrust Acts. The ruling gave member schools more autonomy to negotiate broadcast rights agreements.

- 2009 – Former UCLA basketball standout Ed O’Bannon was a plaintiff in a class action against the NCAA. O’Bannon and the other plaintiffs claimed an EA Sports video basketball game used their likenesses without consent or compensation.

- 2014 – Northwestern University football players petitioned the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to classify them as employees and permit them to unionize and directly benefit from commercial opportunities. The NLRB petition was unsuccessful, but the NCAA and member schools were put on notice about limiting the monetization of NIL by student-athletes.

- 2015 – Federal district and appellate courts upheld the arguments of O’Bannon and the other plaintiffs, ruling that the NCAA’s amateurism rules were an unlawful restraint of trade. As a result, the NCAA increased the grant-in-aid limit to the full cost of attending school and allowed up to $5,000 per year in additional compensation.

- 2019 – California became the first state to pass NIL legislation in the “Fair Pay to Play Act” which prohibited the NCAA or member schools from punishing student-athletes who earn NIL compensation. The new measure was set for enactment in 2023.

- 2020 – Colorado, Florida, Nebraska, New Jersey, and several other states pass laws permitting college student athletes to monetize their NIL. These new regulations are scheduled for enactment in 2022 and 2023.

- 2020 – The National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) passed regulations allowing NIL compensation for its student athletes. The NAIA regulates collegiate athletics at 252 member institutions who field 77,000 student athletes in 27 sports.

- 2021 – In NCAA vs. Alston, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected an NCAA appeal of its antitrust lawsuit, finalizing the lower court decision that the NCAA is not exempt from antitrust regulations. This ruling opened the floodgates for additional academic-related compensation and led to the NCAA’s ultimate decision to quickly adopt an Interim NIL Policy that allowed, for the first time, student-athletes to benefit financially from their name, image, and likeness without fear of NCAA penalty.

- 2022 – The NCAA Board of Directors issued NIL guidance to member schools which reinforced the prohibition of any recruiting incentives offered to student-athletes linked to potential NIL arrangements.

- 2024 – The NCAA’s rule change comes in light of a pending class action lawsuit brought against the NCAA and 10 Division I Ice Hockey schools on behalf of a CHL player. On August 12, 2024, Ryan Masterson brought a class action lawsuit alleging that “as a result of the illegal conspiracy in violation of the U.S. antitrust laws” the NCAA’s rule is an illegal group boycott aimed at suppressing competition between NCAA hockey teams and CHL teams.